In the northern section of Central Park, a recreated natural stream called Montayne’s Rivulet flows into Harlem Meer, a lake with a Dutch name. Prior to the development of Central Park, this stream flowed into Harlem Creek, a waterway that shaped the development of Harlem in its first two centuries, flowing towards the Harlem River along what is today East 107th Street, just south of the recreational pier.

The only above surface image I have of this hidden waterway is a sewer opening on Harlem River at East 107th Street. When there is too much rain, this is where water collected in Harlem Meer and the streets of East Harlem flows out.

Where it flowed

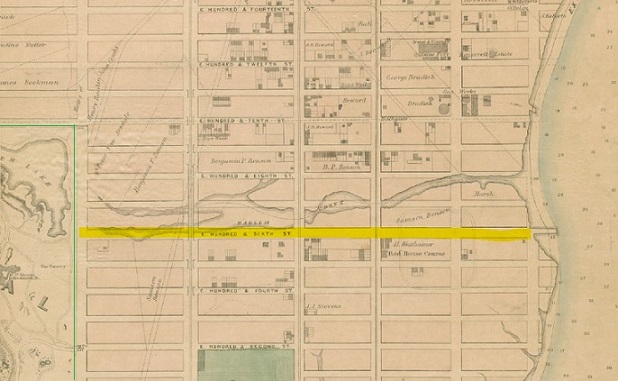

Relying on the good old Viele map of Manhattan, I marked the outlines of Central Park and Marcus Garvey Park; and highlighted all the two-way east-west streets in Harlem, along with the grid-defying St. Nicholas Avenue, as points of reference.

Within Central Park, we see Montayne’s Rivulet flowing towards the park’s northeast corner, joined by an unnamed tributary flowing along the park’s northern border. Harlem Creek begins further north at a spring on West 120th Street between Amsterdam Avenue and Broadway, descending down from Morningside Heights onto the Harlem plain.

At 117th Street, Harlem Creek turned sharply to the south, merging with Montayne’s Rivulet at 109th Street and then turning east, widening into a salt marsh that empties into the Harlem River. The Harlem Marsh was wide enough to be designated in the 1811 Commissioners’ Plan as a public space left out of the grid. But eventually development encroached around the creek, leaving no trace of it on the surface of Harlem.

In its early years

In 1879 author James Riker drew a map that illustrated the colonial landholdings of upper Manhattan. The diagonal line stretching approximately from what are now East 74th Street on the East River and West 129th Street on the Hudson River. New Harlem, named after a city in the Netherlands was intended to be a municipality separate from New Amsterdam at Manhattan’s southern tip. For the first farmers of this community, Harlem Creek was an important source of water and food. A tidal gristmill built on the creek ground grain into flour.

When the English took over the colony, New Amsterdam became New York, and New Harlem was supposed to be Lancaster but the residents never used this new name. A dam was constructed on the salt marsh in 1667, along with a bridge that carried the postal road connecting New York and Boston.

The millpond was purchased by Derick Benson in 1730, and the name Benson’s Hook appeared on maps for the land at the mouth of Harlem Creek. Destroyed during the American Revolution and subsequently rebuilt, it operated until 1827. That year the Harlem Canal Company was chartered, seeking to construct a 60-foot wide canal from Harlem Creek to the Hudson River at Manhattanville. The cost was too prohibitive and subsequent efforts to avoid circumnavigating downtown Manhattan were shifted to the Harlem River and Spuyten Duyvil Creek, which were transformed into a sea level canal in 1895.

The encroaching grid

On this 1848 Mayer & Korff map of the grid-defiant Mount Morris, Fifth Avenue is interrupted by the 70-foot rocky outcropping that was preserved as today’s Marcus Garvey Park. On the lower left of this map is Harlem Creek flowing towards Fifth Avenue at 115th Street. From there it flowed south towards its confluence with Montayne’s Rivulet where Harlem Meer would later appear. This map, from the MCNY exhibit The Greatest Grid shows the future park as the home of Samson Adolphus Benson, whose family owned land along Harlem Creek down to the East River.

With the geographic destiny of Manhattan determined by the Commissioners’ Plan, the rectilinear avenues that start at Houston Street were making their way north.

With the geographic destiny of Manhattan determined by the Commissioners’ Plan, the rectilinear avenues that start at Houston Street were making their way north.

On the 1836 Colton Map of Manhattan, Park Avenue and Third Avenue were crossing Harlem Creek, while to its west, I outlined the borders of Central Park. Within the park, I also highlighted a remnant of the Eastern Post Road which would be demapped when Central Park was commissioned in 1853.

The dotted line on the far right is Second Avenue, which was extended across Harlem Creek in 1837. The two thin maroon lines are the borders of Harlem Common, a public space designated in the 1686 Dongan Charter separating the towns of New York and Harlem.

Avenues bury Harlem Creek

Leaping a generation ahead to the 1867 Dripps map, I highlighted East 106th Street and the outlines of the recently opened Central Park. Lexington and Madison Avenues have not been laid out yet, but every other avenue except First Avenue are now seen crossing the creek. It is no longer a barrier to the northward expansion of the city.

In the 1891 G. W. Bromley survey of Manhattan, the creek is entirely gone, but its shorelines faintly appear. I highlighted them, including the site of Benson’s milldam at Third Avenue. On the left edge of the map, Bromley indicated the path of Eastern Post Road, running diagonally between Madison and Fifth avenues. Notice how in 1891 a third of East Harlem is still undeveloped. Most of the buildings are clustered along Third Avenue. That’s because in 1878 this avenue received an elevated railway, which would keep Third Avenue in its shadow until 1955. That year, Bromley released its last survey of Manhattan, where the outlines of Harlem Creek can still be seen.

Park Avenue at Harlem Creek

The dip in the landscape on this 1870 stereoscopic view looking north was once much deeper and had Harlem Creek running through it. It shows the New York Central (predecessor of Metro-North) train steaming south en route to Grand Central Terminal. The track follows the route of Park Avenue. At the time, the trains ran atop an Old West-style wooden trestle. The hilltop on the left side of the tracks is Snake Hill, also known as Mount Morris, the rocky centerpiece of Marcus Garvey Park.

In 1875, brownstone embankment carrying the tracks between E. 97th and E. 111th Streets was completed. Going north, Park Avenue descends towards E. 107th Street and then rises again towards E. 116th Street. This wall is a vertical habitat of resilient plants that grow out of the crevasses between the stones. The embankment was constructed in tandem with the Park Avenue tunnel below E. 96th Street.

Harlem Creek floods the subways

As my book shows in numerous examples, the city’s hidden streams keep reappearing long after their burial. When the Lenox Avenue subway line was constructed through Harlem, the tunnels kept flooding and older Harlem residents with long memories attributed it to Harlem Creek.

According to New York Times accounts of the flooding, it was determined that the water in the tunnel between 110th and 116th streets was “cold and clear” in contrast to “grimy” sewer water. The first article notes that there used to be a Goldfish Pond at Lenox Avenue and 117th Street, directly in the path of the subway tunnel.

The Independent Town of Harlem

There was a time when the outline of today’s New York City was comprised of numerous municipalities across the future five boroughs. Some of their former Town Halls are still standing, and my friend Joseph Ditta dutifully keeps alive the memory of the Town of Gravesend. Harlem was also once an independent municipality but when it officially became part of New York City is a matter of dispute. Some sources claim that the same Dongan Charter that affirmed Dutch-period property claims in Harlem also incorporated it within the bounds of New York City.

In 1889, attorney John W. Pirsson looked at colonial property records along Harlem Creek to reassert the right of descendants to claim them, publishing his findings in a book.

In 1903, five years after NYC had annexed Queens, Brooklyn, and Staten Island, stockbroker Henry Pennington Toler (1864-1910) took Pirsson’s research a step further, attempting to declare the city’s annexation of Harlem as illegal.

Together with his law partner Harmon de Pau Nutting, they wrote a book, “New Harlem past and present : the story of an amazing civic wrong, now at last to be righted,” a deeply researched and illustrated book making the case for an independent uptown. Above is a logo that appears in the book. Toler tracked down descendants of the colonial patent holders, organized meetings, and filed a lawsuit against the city to recover New Harlem.

To call Toler a character is putting it mildly. Reporting on a November 30, 1903 meeting of New Harlem descendants, the New York Times noted that he went around the streets with a bell shouting “Town meeting!” Among the 2,500 gathered, the majority were Christian Science adherents, including Toler. This led to arguing over religion more than the alleged $3,000,000,000 of land.

“The town of New Harlem was recognized by the New York State Legislature as late as the year 1835… Unless the corporation itself has voted to disintegrate, and such vote of disintegration has been duly placed on record, or a judgment has been rendered in court bringing this corporation to an end… These actions have not been done. Did New Harlem simply lapse out existence as New York City took over its functions? ” -William Toler.

As Henry Pennington Toler delved deeper into Christian Science, his crusade for New Harlem was quietly abandoned at the request of church founder Mary Baker Eddy. Toler’s insanity became more pronounced and he was taken to the asylum on Wards Island. On February 1, 1910, Toler plunged into the East River from the opposite shore from where Harlem Creek was located.

The separatist cause was taken up again in 1932 by Jesse Halstead, who sought to recover a former cemetery property in Inwood on behalf of 3,000 descendants by invoking Harlem’s separate status. Justice John L. Walsh quashed the lawsuit, arguing that New Harlem “passed into the great beyond so many years ago” that only propaganda could give it a “ghost of being.” The last attempt to reclaim Harlem was in February 1942 by Dudley Oliver Osterheld and Philander Betts 3rd. According to one news report, court clerks were so dumbfounded by the New Harlem lawsuit, they mistakenly put “New Haven” on the court’s calendar. Justice Philip J. McCook took the advice of the defendant, Title Guarantee and Trust Company and dismissed the suit.

What’s there today

Between First Avenue and Third Avenue, bound by 106th and 108th Streets are the Ben Franklin Plaza apartments, an affordable co-op development completed in 1960. Taking up 14 acres of land on two superblocks, these 20-story towers contain 1,632 units.

When one thinks of possibilities in daylighting Harlem Creek, few are available as most of the stream bed has been densely developed. Certainly the city can install bioswales along the sidewalks and channel rainwater from Franklin Plaza’s rooftops into containment ponds on its sizable campus. All in an effort to reduce the burden on sewers and reduce street flooding.

Steve Duncan was here

I haven’t gone down there, but urban explorer Steve Duncan did. The Harlem Creek sewer takes most of its water to the Wards Island sewage treatment plant. Only when there is excessive rain does the untreated water flow directly into the Harlem River.

Joe Bataan was here

When it comes to defending East Harlem’s deeply rooted Puerto Rican culture, City Council Speaker Melissa Mark-Viverito is often on hand to unfurl a commemorative street sign, dance at a concert and honor the great salseros, R&B and hip-hop stars who lived in the neighborhood. With Harlem Creek and Franklin Plaza in mind, here’s an old album cover of Joe Bataan standing atop the buried stream bed of Harlem Creek.

One more thing!

In the course of my research on Harlem Creek, I learned that the city of St. Louis, Missouri also has a Harlem Creek that was forced underground a long time ago.

I will tell the story of this Harlem Creek another day.

7 thoughts on “Harlem Creek, Manhattan”